Read an extract from Vuvuzela Dawn

Luke Alfred (co-author of Vuvuzela Dawn: 25 Sports Stories that Shaped a New Nation) shares an anecdote of the Springboks second World Cup victory.

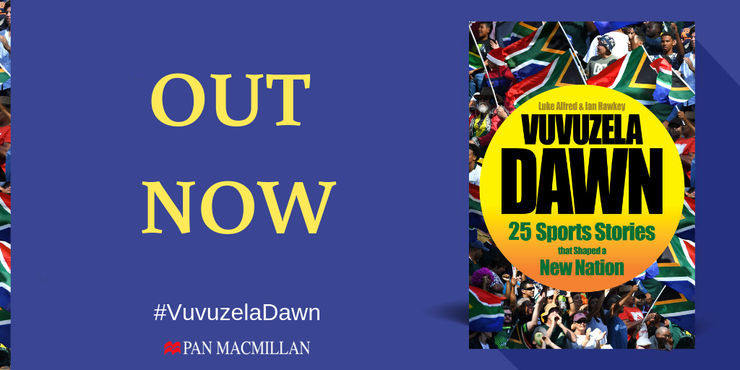

In 2019, South Africa celebrates 25 years of democracy and the freedom that turned the country from a political pariah to one warmly embraced by the world. Nowhere was the welcome more visible, or more emotional, than in sport. From Bafana Bafana’s Africa Cup of Nations win to the fabled ‘438’ Proteas game, Vuvuzela Dawn by Luke Alfred and Ian Hawkey, goes behind the scenes of the great sporting moments and record-breaking triumphs from 1994 to the present. From Caster Semenya and Wayde van Niekerk to Benni McCarthy and Kevin Anderson, from twin World Cup rugby victories to the traumas of Kamp Staaldraad and Hansie Cronjé, the book reveals the sporting dramas and passions that defined a quarter century.

Read an exclusive extract from the book, here.

The 2007 World Cup draw dictated that South Africa’s most important group game was against England, the old foe. If a player can be said to have risen heroically out of the action, taking on dimensions that others didn’t possess, then that man was Du Preez that Friday night against England in Paris. Watching the game again shows that Du Preez was always a second or two quicker than everyone else. He sniped and snapped, running penalties quickly and hoofing the ball back towards England’s posts, causing their monster forwards to stop and turn around. By that time, Jones – a hooker at Randwick in Sydney – had already joined White – a hooker at Jeppe – in an assistant-coaching capacity, and his prints were all over South Africa’s first try: six minutes in and Du Preez initiated a blind-side move off a wheeling scrum, putting right-wing JP Pietersen into space. Pietersen hared downfield as he passed inside to Du Preez, who was half-tackled by Jason Robinson, the England fullback. In the midst of losing his balance, Du Preez remained composed; virtually on his knees, he steadied himself and fired an inch-perfect pass into Smith’s midriff for the Boks’ first try. Du Preez was instrumental in the second try too, Wikus van Heerden in the white scrumcap doing yeoman work by ripping the ball out of England hands at a ruck. A desperate pass from a makeshift scrumhalf found its way to Du Preez in the midfield as he managed to get hold of it a fraction of a second before an on-rushing Englishman. Having evaded the England defender, Du Preez gushed into vacant space, before Pietersen outside of him danced in for his first. At 20–0 to the Boks at halftime, the die was cast for disjointed, cumbersome England, and they eventually lost 36–0. In the post-match press conference, England coach Brian Ashton described Du Preez’s performance as one of the most complete he had ever seen. Not bad from a player who had once taken White huffily aside, demanding to know if he was being omitted in favour of Januarie because of quotas. White says that, in the aftermath of the England win, he realised that the World Cup was now South Africa’s to lose.

Argentina had already beaten France in the tournament’s opening game and the England victory had ensured that South Africa would finish top of their group barring catastrophe against tricky Tonga. When once it might have been assumed that they would play Wales had South Africa finished top of her group, it now emerged that they would face Fiji in their quarter-final – Fiji having beaten Wales by four points in Nantes to finish second behind Australia. ‘You know the feeling,’ says White. ‘You can be close to your hundred as a batsman on 80 not out and still know that you aren’t going to get your century – you just know it. And you can be on 60 not out, still quite a long way off, and know in your bones you’re going to get to those three figures. That’s just how it was for me after we beat England. I just knew.’ Be that as it may, a weekend’s worth of quarter-finals still needed to be decided. On Saturday afternoon in Marseille, England badgered the morefancied Australians to beat them 12–10, while, later that same day in Cardiff, France conjured the surprise of the tournament by sneaking past the woeful All Blacks by a similarly narrow margin (20–18) to set up the first of the two semi-finals. With South Africa’s Tri-Nations neighbours both homeward bound, and South Africa, Fiji, Argentina and Scotland battling for the remaining two semi-final places, the draw suddenly opened up for the Boks like the Red Sea for Moses. The team watched the second Saturday quarter-final in Cardiff from the comfort of their hotel rooms in distant Marseille, in pairs or groups. They lounged on beds or in hotel-room chairs, savouring the All Black defeat. ‘When they lost it was like New Year’s Eve,’ says White. ‘Everyone went absolutely meshuga. Everyone ran onto the balcony of our hotel and started shouting. I was on the road outside and looked back at the curved hotel: he lights were on and everyone was celebrating. It was as though we’d just won the World Cup.’ It had already been a weekend of upsets, and at 20-all three-quarters into the Springboks’ afternoon game against Fiji at the Stade Vélodrome in Marseille the following day, it looked as though Saturday’s motif was making a reappearance. Thanks to Fourie’s early try and a pushover by skipper Smit, the Boks went into halftime 13–3 to the good, but it soon turned sour. An early Fiji penalty, combined with two converted tries, rattled the South Africans badly. Montgomery eased them in front (23–20) at the beginning of the fourth quarter as the match swirled from end to end. Pietersen made a miraculous tackle in the corner and, temporarily, it seemed as if the tide of Fijian white shirts had been tamed. Smith scored after a rolling maul and a hectoring Butch James, playing an increasingly influential role, scored late to suggest the 37–20 victory was comfortable. In truth, it had been a dogfight, full of high tackles and generalised mayhem. The desperate Fijians flooded the breakdown after halftime and began to exploit space in the disorganised Bok midfield. Smit’s men missed their tackles and temporarily lost their shape as referee Alan Lewis appeared reluctant to blow his whistle. It was a perilously narrow escape.

Still, the Fiji game was an impressive achievement for Smit. He scored a try and initiated the bollocking from beneath the posts when Fiji were in the midst of drawing level just before their second try was converted. When Matfield was high-tackled during a passage of play shortly thereafter, prompting no sanction from Lewis, Smit was piqued. ‘See what happens when you make those sorts of mistakes,’ he rasped at Lewis, later going on to give his side another rousing pep talk when Johann Muller replaced Botha late in the day. At the Stade de France in Paris later that evening, Argentina beat Scotland 19–13, meaning that South Africa would face Argentina in the second semi-final. Taking place a week after their quarter-final defeat of Fiji, the semi was a salty, slightly anticlimactic affair, with incessant volleys of ‘seewhat-you-can-do-with-this’ kicking and mandatory knock-ons from two overwrought sides. The Springboks were calmed by an early intercept try by Du Preez and the fact that Juan Martín Hernández and Felipe Contepomi, at flyhalf and inside-centre respectively, both had wretched evenings. Contepomi flung out the Du Preez intercept pass and it was Hernández who knocked on after a long speculative pass from Agustín Pichot, his fumbling leading to Rossouw’s try, South Africa’s third, after Bryan Habana had burst free for their chip-’n-chase second. Three tries played two penalties (24–6) at halftime, as the South Africans romped home 37–13 winners. England beat France in a 90-minute arm wrestle in the other semi-final – so it was that the green machine rolled to Paris for their second encounter with England. The nervous energy in the week prior to the final was palpable. Everyone watched the clock – they couldn’t help it. The hours passed more slowly than usual and in the first couple of days of the week the Boks trained grindingly hard. Everyone was restless. In the expectation, tempers frayed. Eventually, in a neat inversion, captain pulled coach aside. ‘Enough is enough, Jake,’ said Smit forcefully. ‘No more drills. No more extra work. You’re becoming a nervous wreck and it’s contagious – you’re making the team nervous. Calm down. Ease off on the workload. Stop allowing your emotions to get the better of you.’ Jones, by now essential to the system, was of a similar view. He had been Wallaby coach when they lost the 2003 World Cup final to England in Sydney, and had first-hand experience of pre-final nerves. He told White that what the players needed most was to hear his voice. He needed to project. His body language needed to be crisp and erect. He should be calm, boosting their egos, telling them what they wanted to hear in clear, positive language. ‘Then, suddenly, on the Thursday, they wheel Jones out to the press conference – we haven’t seen him at all up until that stage,’ says Ray. ‘And he’s amazing. It’s a master class. He’s funny. He has a gentle go at England. He even manages to get a dig in at the All Blacks. He unpacks the tournament and presents the Springboks in a new light.

The press laps it up.’ Meanwhile, there was angst aplenty in the England camp. Ashton was accused of being disengaged. Leaving the players to their own devices might work under ordinary circumstances, but days before the World Cup final, it smacked of neglect. Despite this, England miraculously found themselves, and were stabilised by making crucial personnel changes and positional shifts from the earlier game against South Africa. For the final, Mike Catt made way for Jonny Wilkinson at flyhalf, shuttling into the centre with Mathew Tait; Andy Farrell was displaced and so, too, was Shaun Perry, the scrumhalf. The new halfback pairing of Andy Gomarsall and Wilkinson was an improvement on the group game, although Wilkinson’s two drop kicks in the final sailed wide. The final is best described by what it wasn’t. It wasn’t a free-wheeling romp as, say, the five-try feast between the All Blacks and the Wallabies was in 2015. Neither was it a great rugby spectacle, one recalled by the purists as part of the canon of great games. And it certainly wasn’t a repeat for Du Preez of his brilliant game in the group stages. He was frequently swamped by England’s loose forwards in the final, his comparative lack of authority contributing to South Africa’s staccato rhythm. Other than a prolonged period towards the end of the first half during which they threatened to score, theirs was a doggedly brave defence of Montgomery’s four penalties and a long-range fifth from Frans Steyn. Courageous and frequently brutal, it was never pretty. For all this, the final was pulsating and dramatic, resting as it did on Tait’s quicksilver break just after halftime as he winkled through the Bok midfield after a poor pass by Gomarsall had bobbled to no one in particular. Matfield, retreating, pounced on Tait’s back like a lion on a buffalo, but by this stage the ball had already been shovelled to the winger Mark Cueto, who appeared to score despite Rossouw’s lunging tackle. The consultations with the video referee took an eternity. Eventually French referee Alain Rolland decided that Cueto’s foot had touched the line as he dotted down. The try was disallowed, the Boks preserved their 9–3 halftime lead and added two more penalties for good measure. England poached a penalty themselves but, finally, after England had pressed and pressed, Rolland blew his whistle.

South Africa had won the final 15–6. There was rejoicing throughout the land. White’s insistence that the Springboks would win the 2007 World Cup functioned as a bull’s eye at which senior players – Smit, Du Preez, Matfield, Smith – took aim. It also amounted to nothing less than a deep reading of the sport in South Africa. White knew that rugby was congenitally unstable, containing booby traps, quicksand and marshy ground. By the time White was recalled from the European tour of 2006 to account for himself and his string of losses, he was thoroughly gatvol of interference and second guessing. ‘“You are coming back?” asked Steyn before I left France to come home,’ remembers White. ‘I arrived and ended up sitting in the corridor while they [the suits] had their meeting,’ he says. ‘I sat waiting for 45 minutes and then they all trooped off for lunch.’ In the end, none of this mattered. Viewed from afar, White and his team’s narrative has an arc unprecedented in the annals of the South African game. An Afrikaner boy with an English name, White was a hooker at a Milner-type English school. An English boy with an Afrikaans name, Smit – another hooker from a prototypically English South African school – became his captain. The trinity was complete when Jones – a third hooker and perpetual outsider who lived on his rugby wits – was drafted into the coaching staff at the last minute.

Victorious skipper John Smit holds the 2007 Rugby World Cup aloft, flanked by President Thabo Mbeki and Ricky Januarie.

PHOTO: ANNE LAING

Watch the trailer for Vuvuzela Dawn

Vuvuzela Dawn

by Luke Alfred

In 2019, South Africa celebrates 25 years of democracy and the freedom that turned the country from a political pariah to one warmly embraced by the world. Nowhere was the welcome more visible, or more emotional, than in sport. Vuvuzela Dawn tells the stories of that return.

From Bafana Bafana’s Africa Cup of Nations win to the fabled ‘438’Proteas game, we go behind the scenes of the great moments and record-breaking triumphs from 1994 to the present. From Caster Semenya and Wayde van Niekerk to Benni McCarthy and Kevin Anderson, from twin World Cup rugby victories to the traumas of Kamp Staaldraad and Hansie Cronjé, Vuvuzela Dawn reveals the sporting dramas and passions that defined a quarter century.