The Soweto Uprisings: Events as they unfolded on 16 June 1976

When the Soweto uprisings of June 1976 took place, Dr Sifiso Mxolisi Ndlovu, the author of this book, was a 14-year-old pupil at Phefeni Junior Secondary School. With his classmates, he was among the active participants in the protest action against the use of Afrikaans as a medium of instruction.

Contrary to the generally accepted views, both that the uprisings were ‘spontaneous’ and that there were bigger political players and student organisations behind the uprisings, Dr Sifiso Mxolisi Ndlovu's book shows that this was not the case. Using newspaper articles, interviews with former fellow pupils and through his own personal account, he provides us with a ‘counter-memory’ of the momentous events of that time.

In The Soweto Uprisings: Counter-Memories of June 1976, Dr Ndlovu also analyses the historiography of the uprisings as well as reflects on memory and commemoration as social, cultural and historical projects. Read an extract of the events as they unfolded on 16 June 1976.

Events as they Unfolded on 16 June 1976

The weekend before the march, a meeting was held between students and some BPC members to finalise strategy. The student Action Committee plan was to stage a peaceful march – with students from all over Soweto congregating at Orlando Stadium and then from there to proceed to the regional offices of the Department of Bantu Education in order to deliver a memorandum reflecting student grievances. The principal route passed through the Orlando West precinct because of the symbolic role of Phefeni Junior Secondary School. The students had decided at their meeting on 13 June that they would march by ‘any route leading to Phefeni Junior Secondary School’ to demonstrate their solidarity with students on strike. Once gathered at Phefeni Junior Secondary School, on their way to the Orlando Stadium, Tsietsi Mashinini would address the students. Morobe reminisces: ‘Our original plan was just to get to Orlando West [Junior Secondary School], pledge our solidarity, sing our song and then we thought that is it, we have made our point and we go home … Neither did we expect the kind of reaction that we got from the police that day.

The Cillie Commission Report has been used here to reconstruct the events that took place that day:

07h45: Colonel J.A. Kleingeld, Station Commander of the Orlando Police Station ordered all available policemen to be on stand-by. A Black sergeant who was sent to inspect saw several groups of marchers. The march was proceeding along Xorile Street from north to south. The sergeant notified the Orlando Police Station that children were marching in the streets.

07h50: Brigadier S.W. le Roux, Divisional Commissioner for Soweto, received information concerning the marchers from the local Chief of Security and ordered six station commanders to send out patrols.

08h00: Scholars carrying placards gathered at Naledi High School. Tebello Motapanyane led the student march to Orlando West past Thomas Mofolo Secondary School and the Morris Isaacson High School. Scholars from Tladi, Moletsane and Molapo Secondary Schools also arrived and took part in the protest march.

08h30: Colonel Kleingeld requested reinforcements and issued revolvers and pistols to his men. With 48 policemen, 40 of whom were black, he went past the Orlando Stadium to Uncle Tom’s Hall, where scholars had gathered … At this stage, Brigadier Le Roux realised that the situation was explosive. He had too few men – between 300 and 350 – at his disposal to control the situation.

10h55: A West Rand Administration Board (WRAB) official, J.B. Esterhuyzen, was driving along Khumalo Street (in Orlando West) when he was attacked by youths. He tried to escape from his car, but was surrounded by youths and beaten to death. During this period delivery vehicles, government buildings and cars were pelted with stones and set on fire. Trains were also attacked.

11h20: As word of police brutality spread around Soweto, WRAB was launching a new sheltered employment workshop at Orlando East. The function was attended by among others Dr L.M. Edelstein, the chief welfare officer. Word reached them of the uprisings and Edelstein left by car for the youth centre in Central Western Jabavu. By then his car had been damaged by stones. He ran to his office and locked the door. Another WRAB official, R. Hobkirk, was trapped in another office. The protesters forced their way into Edelstein’s office, and dragged him outside. Hobkirk escaped and was protected by members of the local community. Edelstein was beaten to death. Two 18-year-old scholars, K. Dhlamini and L.J. Matonkonyane, were later charged with the murder of Edelstein but acquitted.

12h00: Police refused white journalists entry into Soweto. They obtained information about the uprising from their African colleagues.

12h15: An unsuspecting African social worker from the Department of Bantu Administration and Development was hosting a white woman student researcher. Students on Orlando West Bridge stopped their car and threatened to assault the researcher. She was protected by well disposed students and placed in the care of a local clergyman.

12h30–13h00: SABC camera crew and newsmen were allowed to accompany police patrols in Soweto. Bottle stores at Phefeni/Orlando West were looted and set on fire. WRAB buildings were also targeted. Police continued to use tear gas and live ammunition to control the situation.

14h00: A large contingent of paramilitary police reinforcements arrived at intervals as looting and arson continued with criminal elements/tsotsis taking advantage. A senior police officer undertook an inspection flight by helicopter over Soweto. People were scattered and gathering in several places. There was chaos; vast parts of the area were under smoke, with buildings and cars on fire. Three white medical doctors were trapped at Mofolo; a vehicle was sent to their rescue.

14h30–17h00: As the burning and looting continued, wounded and shot people continued streaming to Baragwanath Hospital and various local clinics. Medical staff was overwhelmed. The police seemed to be shooting without warning and indiscriminately. Looting, arson and violence continued. WRAB offices and its bottle stores at Orlando West and Orlando East were set on fire. So too were the WRAB offices in Meadowlands and Diepkloof. Arson and looting continued at Nhlazane, Moroka/Rockville, Mofolo, Chiawelo, Senaoane, Zola, Moletsane and Jabulani. Post offices, the White City library, the clinic in Senaoane, and the Mapetla hostel were attacked. The police arrested a number of people and more people were wounded and killed.

At 15h30 Colonel Theunis ‘Rooi Rus’ Swanepoel arrived in Soweto with three officers and 58 policemen. They divided into two task forces. The force under Swanepoel came up against the protesters around Uncle Tom’s Hall. The crowd numbered about 4 000 and was dispersed by the police who fired at them.

17h00–20h00: Violence, death and arson continued. Burned motorcars were used to block roads and railway tracks, as police used rail and road to gain access to other parts of Soweto.

19h00: Police were split into smaller groups, and assigned specific tasks. Major-General W.H. Kotze, Divisional Commander for the Witwatersrand, accompanied by a number of armed men, went by car from Moroka Police Station to Jabulani Police Station, as radio communication between the two stations was poor.

21h00: A meeting of the Soweto Parents’ Association was held in Dr Nthato Motlana’s consulting rooms to discuss the events of the day. Along with Motlana, Winnie Mandela, Tebello Motapanyane, a student, and R. Matimba, a teacher, were among those present. Mandela suggested that a mass funeral for police victims be held on Sunday, 20 June. The service was later prohibited.

From the official records, the paramilitary police who had arrived in Soweto during the day were given orders to shoot to kill; law and order was to be maintained ‘at any cost’. The police shot dead another 11 people before that day ended; 93 more people were shot dead by police over the next two days. The Soweto Parents’ Association (SPA) called a meeting to discuss plans for a mass funeral for the victims of the uprising and for providing financial aid to afflicted families. The SPA was formed on 21 July 1976 as an umbrella organisation of representatives from SASM, SASO, the Post Primary Principal’s Union, Black Social Workers Association (BSWA), Black Community Programmes (BCP), YWCA, YMCA, Parents Vigilante Committee, South African Black Women’s Federation and the Institute of Black Studies. Almost all the representatives were residents of Soweto, even though some of the organisations were national in character. The name changed to Black Parents’ Association (BPA), whose first secretary was Aubrey Mokoena; it embraced parents in other affected areas such as Alexandra Township as protest expanded to various other areas. The Johannesburg Magistrate’s office turned down BPA chairman Reverend Manas Buthelezi’s application for permission for a mass funeral. Minister of Police, Jimmy Kruger, declared: ‘It is known that black power organisations are behind the move to hold the service. There was division in the BPA executive over whether to proceed in spite of the ban. A compromise was reached in the decision to arrange one symbolic funeral – that of Hector Pieterson.

------------------------

Born in 1963, Hector Pieterson became the iconic image of the 1976 Soweto uprising in apartheid South Africa when a newspaper photograph by Sam Nzima - of the dying Hector being carried by a fellow student - was published around the world. Explore the story behind one of the most influential image that changed world via TIME:

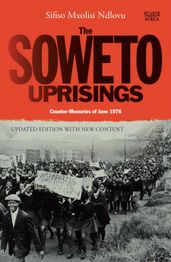

The Soweto Uprisings

by Sifiso Mxolisi Ndlovu

When the Soweto uprisings of June 1976 took place, Sifiso Mxolisi Ndlovu, the author of this book, was a 14-year-old pupil at Phefeni Junior Secondary School. With his classmates, he was among the active participants in the protest action against the use of Afrikaans as a medium of instruction.

Contrary to the generally accepted views, both that the uprisings were ‘spontaneous’ and that there were bigger political players and student organisations behind the uprisings, Sifiso’s book shows that this was not the case. Using newspaper articles, interviews with former fellow pupils and through his own personal account, Sifiso provides us with a ‘counter-memory’ of the momentous events of that time.

This is an updated version of the book first published by Ravan Press in 1998. New material has been added, including an introduction to the new edition, as well as two new chapters analysing the historiography of the uprisings as well as reflecting on memory and commemoration as social, cultural and historical projects.

Hero Image: Peaceful young schoolchildren, smiling, singing, marching and displaying a clear message intended for the Department of Bantu Education authorities. This was before the violent intervention of the police.